In hindsight, travel drama seems to announce the beginning of many of our vacations. Once, during an Andaman trip, I forgot to collect the keys of our luggage at airport security, resulting in a late-night hunt for a key maker in Chennai.

This trip had its own opening act.

After landing in Delhi from Pune, we began our road journey to Agra at around midday. A casual conversation with the taxi driver suddenly turned serious when we mentioned our plan to visit the Taj Mahal the next day. He calmly informed us that the Taj Mahal is closed on Fridays.

That moment—equal parts disbelief and panic—forced instant improvisation. We decided to visit the Taj the same day, Thursday. A hurried check-in, quick freshening up, and a race against the clock followed. The entry gates close at 5 pm, and we were the last five people allowed in before the shutters rolled down.

We had just made it.

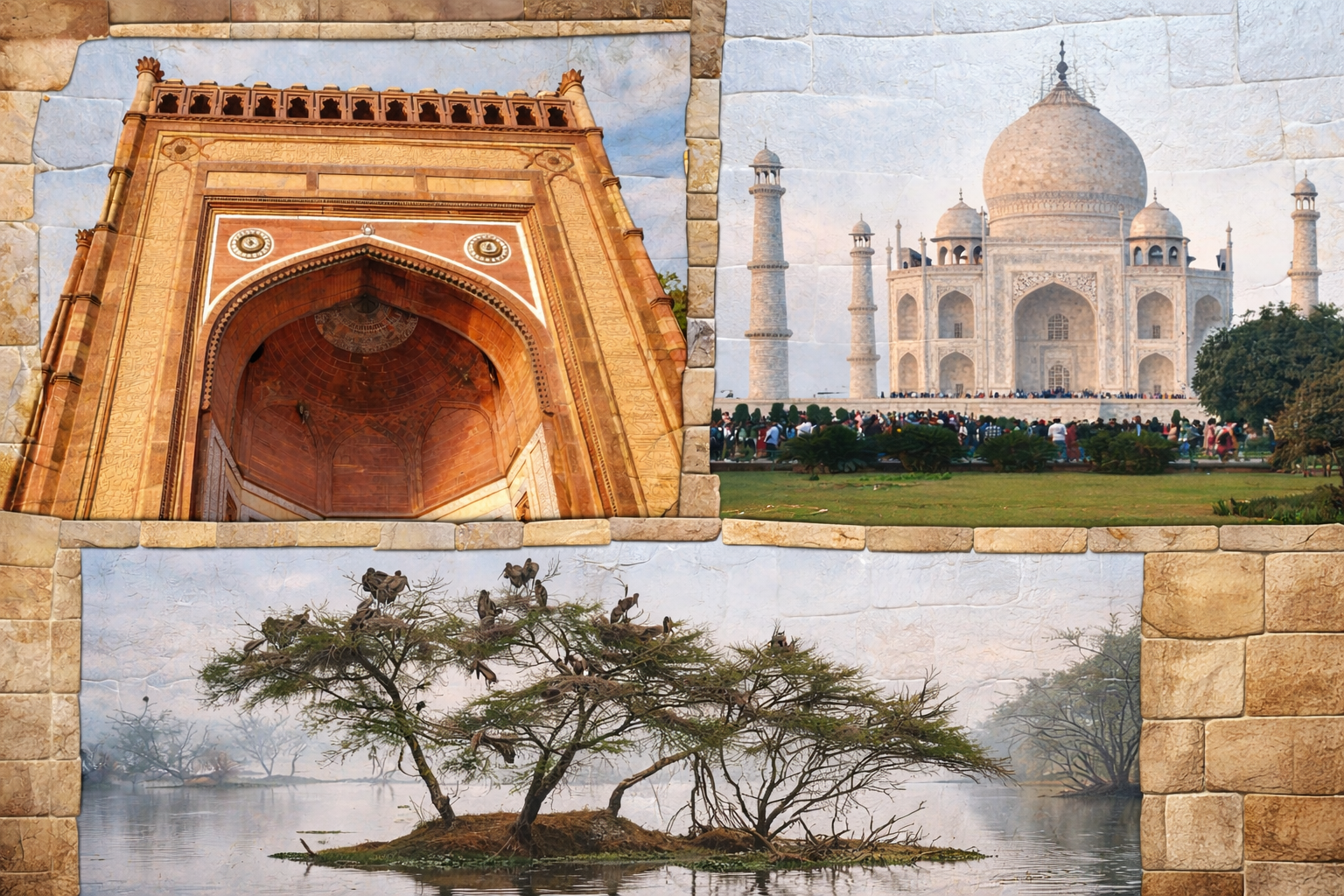

Seeing the Taj Mahal in person is fundamentally different from seeing it in photographs all one’s life. The white marble, the semi-precious stone inlay, the symmetry—everything stood in quiet confidence. Despite the late entry, we still had a couple of hours inside.

We were underprepared for the realities of a place like the Taj Mahal. Along with awe comes crowd, commerce, and persuasion.

Guides quoted steep prices and gently nudged us toward “optional” shopping stops. Photographers—mercifully—offered digital copies, which suited us better than printed ones. Still, without a clear agreement, they could easily flood you with prints and inflate the bill. We learned quickly: clarity upfront matters.

With some freedom given, our photographer ended up taking 80 photographs of the five of us—in every possible combination. It was excessive, but we didn’t regret it. My philosophy while traveling has always been simple:

I would rather spend a little extra money than lose an experience.

Shopping for petha, marble artifacts, and stone carvings revealed Agra’s rich craftsmanship—but also its storytelling excesses. Claims of “17th-generation artisans” and so-called “government shops” later proved to be creative marketing rather than facts. We smiled, accepted it as part of the experience, and moved on. Later in the trip, when we saw peacocks, I could not resist quipping that this particular one must surely be the 74th generation descended directly from the peacocks that once strutted through Akbar’s gardens.

Agra has more to offer beyond its most famous landmark. The tomb popularly known as Baby Taj was well worth the visit. Its architecture is delicate and thoughtful—the dome shaped like a treasure chest, a serene garden layout, and the Yamuna flowing alongside, echoing the larger masterpiece downstream.

Mehtab Bagh, though not in its best shape, offered something else: a different perspective. Seeing the Taj Mahal from across the Yamuna—less crowded, more contemplative—was worth the visit, if only to pause and look back.

The following day brought us to Agra Fort, and this time we were better prepared. Fewer photographers, clearer expectations, and—most importantly—a genuinely knowledgeable guide. He took his time, explained patiently, and his historical insights stood up to scrutiny.

Visiting Fatehpur Sikri after Agra Fort was particularly illuminating. Built under Akbar, the similarities were evident—Diwan-e-Aam, Diwan-e-Khaas, royal residences—yet expressed differently.

What I hadn’t fully absorbed from school textbooks was that Fatehpur Sikri, despite years of construction, was never truly lived in for long. Water scarcity forced abandonment, sending the empire back to Agra.

It stood there—magnificent, ambitious, and underutilized—a reminder that even grand visions depend on basic resources.

Fatehpur Sikri was also overwhelming with crowds and self-appointed guides—many acting more like brokers for photographers and shrine donations than historians.

At the Dargah, donation requests bordered on extortion. Still, I didn’t want to spoil the moment.

I am not an atheist, but I stand near the border. I don’t usually ask for wishes. Yet watching my family engage in the ritual of asking for three wishes, inspired by Akbar’s belief, I joined in.

What surprised me was not belief—but reflection.

Asking myself, “What are the three things I truly want right now?” turned out to be a powerful exercise. Rational or irrational, it forced clarity.

It also reminded me of a childhood memory—writing a wish at the Manokamana Mandir in Darbhanga, long after I had already prepared for a scholarship exam. When the results came, I had qualified. Magic for a younger mind—logic for an older one.

After three days steeped in Mughal history, we moved to Bharatpur, crossing into Rajasthan.

I had always known, vaguely, that Bharatpur had a bird sanctuary. Nothing more. What followed turned out to be one of the most enriching phases of the trip.

Only e-vehicles and tongas are allowed inside the sanctuary. The absence of engine noise changes everything. Sounds become sharper, and the place immediately feels more respectful to its inhabitants.

It was a rare treat to encounter so many birds that we do not commonly see around us. Many had migrated from other countries, while others had travelled from distant regions within India. Winter, we were told, is when the sanctuary comes fully alive, hosting these visitors for a few precious months. By March, most would begin their return journeys. Knowing this added a sense of timeliness to the experience—we were not just watching birds, but witnessing a seasonal convergence that would soon dissolve.

Storks were the most immediately noticeable presence in the marshland. Almost every tree rising out of the water carried four or five nests, each hosting chicks in various stages of growth. In sharp contrast stood a heron in shallow water—so motionless that it could easily be mistaken for a sculpture. I waited for minutes just to reassure myself it was alive, rewarded only by the slow blink of an eye. I also learned, for the first time, that ibis was not merely a hotel chain name, but a bird I could actually see and observe. One personal surprise came with the Yellow-footed Green Pigeon. I discovered that it is the state bird of Maharashtra, despite having born and lived there for years. Snakebirds dried their wings in their characteristic poses, while coots glided quietly across the water, unhurried and unbothered.

Until this visit, three names lived separately in my mind: Salim Ali, the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), and Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary. Bharatpur quietly stitched them together.

Our guide mentioned—almost in passing, but with unmistakable pride—that he had worked with Salim Ali for a couple of years. The name came up repeatedly during the walk, each time with a sense of reverence. That alone was enough to spark curiosity.

Salim Ali lived well into his nineties, born in the late nineteenth century, witnessing the British era and then independent India. His career evolved with the nation itself—from studying birds under colonial rule to shaping conservation priorities in a young democracy. The challenges changed; the purpose did not.

What stood out most, however, was not just his contribution as an ornithologist, but as a writer. His writing carries precision without dryness, authority without arrogance, and learning without heaviness. It is scientific, literary, and quietly entertaining at the same time.

By the end of the day, I found myself buying one of his books. As the year draws to a close, it feels fitting to end it in the company of a man who taught generations how to look closely—at birds, at nature, and at responsibility itself.

Was it really a vacation if you came back tired?

There is an old, well-worn joke people repeat almost as a badge of honour: “The vacation was so exhausting that I now need another vacation.” It gets a laugh every time—but it also quietly exposes a misunderstanding of what rest actually is.

We tend to equate rest with physical inactivity. By that definition, a vacation that involves walking, exploring, learning, or adapting feels like a failure. Yet the best part of a vacation is rarely physical rest. It is the rest given to routines—the temporary suspension of predictable schedules, familiar roles, and repetitive decisions.

When routines loosen their grip, something important happens. The mind stretches. It wanders. It absorbs new knowledge without effort—history that was once confined to textbooks, ecology that comes alive through birds and wetlands, people and practices that don’t mirror our own. Learning happens not through intention, but through exposure.

Equally important is stepping out of the comfort zone. Travel places us in unfamiliar systems—different languages of bargaining, different social cues, different rhythms of life. Even small acts, like navigating a new city or trusting an unknown guide, gently train adaptability. On this trip, something as simple as riding an e‑bicycle inside the Bharatpur resort became a quiet mastery experience—a reminder that learning does not stop just because we are away from work.

Psychologist Sabine Sonnentag and her colleagues describe recovery as resting on four pillars: relaxation, control, mastery experiences, and mental detachment from work. Think of them as mental vitamins. Vacations rich in all four are like nourishing meals; those that offer only passive relaxation are closer to empty calories.

The museum, the movement, and the return

The day before the sanctuary visit, we explored the Bharatpur museum. Like many others—weaponry, paintings, royal narratives—it didn’t stand out, but it offered a quiet walk through time.

And like every good vacation, this one left me changed.

I came back a little more mature.

A little more humble.

And a little wiser to the ways people exploit—without letting that bitterness steal the joy.

For now, the journey—from marble to migratory wings—feels complete.

Subscribe to my newsletter, to get tips like this and more, directly in your inbox!